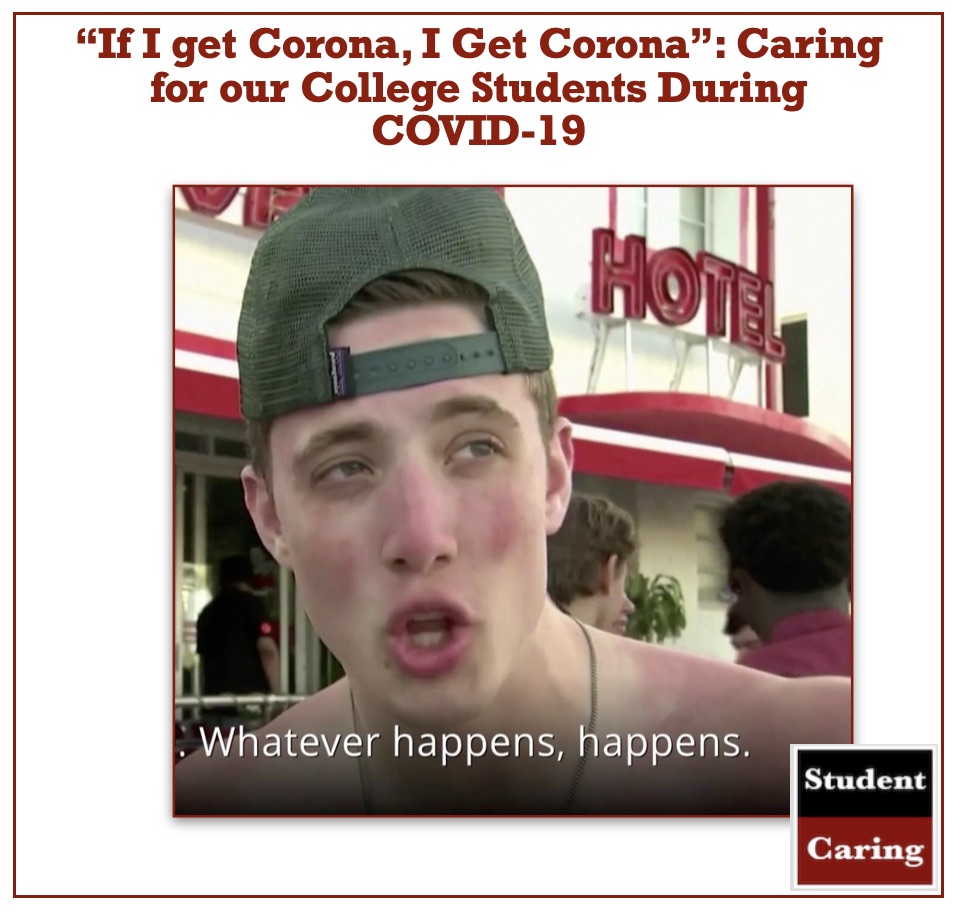

Perhaps rightfully so, much of the rhetoric around COVID-19 has stressed the dangers for those over the age of 65 and/or for those whose immune systems are compromised. This has left many of those who fall into the “young adult” category, a demographic already predisposed to leaning into their assumed invincibility, feeling invulnerable to the disease. And while it’s true that COVID-19 isn’t, statistically speaking, a death sentence for younger folks, they are no less susceptible to contracting and spreading the disease, effectively passing the death-sentence buck onto someone immunocompromised or someone that falls into the age bracket of, say, their parents. An example, albeit an egregious one, of one such college student’s brazen disrespect for the disease is Mr. Brady Sluder, whose recent social blunder has awarded him Internet infamy. While on spring break in Florida, he was caught on camera saying, “If I get corona, I get corona. At the end of the day, I’m not going to let it stop me from partying. You know, I’ve been waiting, we’ve been waiting for Miami spring break for a while, about two months we’ve had this trip planned – two, three months – and we’re just out here having a good time. Whatever happens, happens.” If you haven’t seen the video, take a look here.

Perhaps rightfully so, much of the rhetoric around COVID-19 has stressed the dangers for those over the age of 65 and/or for those whose immune systems are compromised. This has left many of those who fall into the “young adult” category, a demographic already predisposed to leaning into their assumed invincibility, feeling invulnerable to the disease. And while it’s true that COVID-19 isn’t, statistically speaking, a death sentence for younger folks, they are no less susceptible to contracting and spreading the disease, effectively passing the death-sentence buck onto someone immunocompromised or someone that falls into the age bracket of, say, their parents. An example, albeit an egregious one, of one such college student’s brazen disrespect for the disease is Mr. Brady Sluder, whose recent social blunder has awarded him Internet infamy. While on spring break in Florida, he was caught on camera saying, “If I get corona, I get corona. At the end of the day, I’m not going to let it stop me from partying. You know, I’ve been waiting, we’ve been waiting for Miami spring break for a while, about two months we’ve had this trip planned – two, three months – and we’re just out here having a good time. Whatever happens, happens.” If you haven’t seen the video, take a look here.

Except for those adept in the art of homeschooling, education has largely been the purview of those who take up the profession of teaching. Often, when we write about education, we write to teachers because teachers make decisions about what happens in the classroom. In this unprecedented moment, however, we write to a broader audience as the space of the “classroom” is shifting somewhat abruptly and on a massive scale (yes, distance learning has existed in some form for a very long time – how about correspondence education in the 1800s!? – but most students elected into these and other, more contemporary forms of distance learning, like online classes). Although we still write to teachers (especially as they have been asked to shift much of their pedagogical strategies and materials), we also write to parents/guardians, families and friends, who now may be forfeiting their kitchen tables to be makeshift work stations. How best can we care for these students in this time? As reckless as Mr. Sluder’s comments are, they also communicate a great desire to find normality and joy in the chaos. How can we best do that for our students?

As I’m sure you can guess, the Internet exploded with condemnations of Mr. Sluder’s brash comments: “Does he have a clue!”; “I wonder if he’s thought about his parents and grandparents – and the rest of us!”; “America’s best and brightest. We’re doomed.” There’s no shortage of public opinions about all the ways in which Mr. Sluder’s statements are a problem. All you have to do is read the video’s YouTube comments, which we do not recommend, to get a feel for the various gradations of displeasure slung Mr. Sluder’s way, from mere annoyance to outright vitriol. What was your reaction?

We’re concerned for Mr. Sluder not just because he’s opening himself up to unnecessary health risks (a CDC report as of March 18th shows that nearly 40 percent of patients sick enough to be hospitalized fall in the 20 – 54 age range), and not just because he’s contributing to a culture of irresponsibility and apathy, but also because the Internet never forgets. When a 13-second video clip goes viral, especially when it can become associated with a significant time in history like the one we’re in, it takes on a life of its own – a long–life which can influence and remain in the memories of millions of people. For years to come, future friends, significant others, colleges, and employers may google this young man’s name to find a very particular version of Sluder, memorialized forever, and judged harshly as selfish, stupid, perhaps even morally corrupt, rather than merely uninformed and riding the waves of youth. Although it’s completely likely that the Internet outrage will die down as soon as the next big YouTube blunder goes viral, search engines will continue to connect “Brady Sluder” with this video for a very long time (and perhaps for forever if the U.S. doesn’t catch up to the EU’s “Right to be Forgotten” laws). Thank you Internet! (These authors are certainly grateful that some of what we said when were young adults didn’t get captured on video!) Perhaps we’re not the only ones concerned for Mr. Sluder. Just days after his splash (or belly flop) into Internet fame, The New York Times ran a piece on Mr. Sluder’s public apology. Read it here.

Mr. Sluder’s video, the indelibility of his statements, and the smorgasbord of castigating responses all bring many issues to the fore; how can we better educate young people around this unprecedented cultural moment? How can we support our college students’ mental and emotional health during this time? And how can we have greater empathy for what might be considered thoughtless remarks? One of Mr. Sluder’s comments seems particularly easy to relate to: “At the end of the day, I’m not going to let it stop me from partying.” Who among us hasn’t had that thought after working hard? (College is hard work!) Who among us would rather not deal with the many restrictions being placed upon us during this pandemic? Most of us would rather not be mired in worry and/or fear, or be subjected to loneliness in the name of social distancing. Who really wants to wash their hands raw? Don’t you just want to party!? We do! These past weeks, we’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how to party when the coronavirus is no longer a danger.

It seems that what Mr. Sluder needs, what all college students need, is a bit of empathy in this wild time of unknowability. This isn’t a groundbreaking argument. In his 2017 article, “Teaching Physics with Love,” Matthew J. Wright discusses an idea often left out of STEM classes: Love. In fact, Wright often tells his students, “I love you,” and argues that “love of students requires time and patience.” Eleni Damianidou and Helen Phtiaka in their 2014 article, “A Critical Pedagogy of Empathy: making a better world achievable,” studied the extent to which students were able to “disseminate self-gained knowledge and thoughts with a view to creating a better future” after experiences where their teacher spent intentional time trying to understand the students’ lives. In 2016, Eric Leake wrote, “Writing Pedagogies of Empathy: As Rhetoric and Disposition” where he discusses the study of Rogerian argumentation in the classroom as a way to centralize “empathic listening” as a “potentially transformative means of communication.” If educators and researchers found reasons over the last 10 years to advocate for a pedagogy of empathy, then we’re positive our current cultural moment, where our realities are ever presently shifting under our feet, could also benefit from such instructional strategies.

Can we find ways to empathize with Mr. Sluder, and by extension, the rest of our young college students during this time? Even while hundreds of thousands of people worldwide have contracted the disease, and seventy five thousand have died (as of April 7; see the current count here), and even as the economy slows to a halt leaving many of us paralyzed in fear by what this might mean, and even as our own individual life experiences have been disrupted in a variety of ways very specific but perhaps not so singular, can we still hold space for the lives of our college students? Can we empathize with Mr. Sluder’s desire to have fun? Is he perhaps saying the thing we’d all like to say?

Colleges are, by design, challenging for students. Imagine working in a stressful, deadline driven environment (that somebody is paying for), with uncertainty about your future and, all of the sudden, just before a time of celebration, it all stops! (But also, not really…). Overnight, most students were told:

- Move out of your dorms, go home and don’t come back until next fall.

- All of your classes will now be online.

- You have a spring break, but not really.

- Your commencement ceremony is cancelled.

Most students didn’t get an opportunity to say goodbye to each other or to their professors. Many couldn’t take their finals or, in any significant way, finish out their quarter/semester classes they’d worked so hard toward. Some students were plucked from their study abroad programs early while others had their study abroad programs completely canceled. Theater shows that were supposed to happen never did. College sports went on hiatus. Many students had rigorous plans for their next quarter/semester, all of which are now up in the air.

Any one of these items by itself is a significant disruption to learning, never mind the intense social implications of such a shift, but all of them at once necessitates an intentional and robust response of deep care for our students.

10 Ways you can care for college students.

- Recognize they are going through a difficult time, ask them how you can help, then really listen. For tips on improving your listening game, check out this article on “Reflective Listening Techniques,” written by Dr. Adrienne Boissy, MD, MA, Chief Experience Officer of Cleveland Clinic Health System and a staff physician in the Center for Ethics, Humanities and Spiritual Care.

- Understand that school, in some cases, is not their first priority; they may have life circumstances that come first at this time (monetary difficulties, familial obligations, mental/emotional health concerns, etc.). Understand and have patience for the fact that your students, like you, have full lives that are every bit as complicated as your own. We’re all in this together.

- Understand that not every college class will convert well to being taught online. Have patience with yourself so that you can extend that patience to other people, namely your students. But also, consider Kevin Gannon’s argument that “Teaching Online Will Make You a Better Teacher in Any Setting” and embrace the challenge of translating your course into a digital format.

- Help them to prepare for classes online by supporting them with technology through careful instructions and/or links to resources that might help them navigate the tech. Also, be patient as they learn how to use this new technology. Acknowledge that this is new and that it’s perfectly acceptable that everyone is learning together and that they might have questions, and that’s okay, too. You might also suggest best-practices for creating a “work space” for themselves; suggest creating a quiet, comfortable space (if possible). Take a moment to discuss some best practices for how to succeed while taking an online class. You might just share Northwestern’s “8 Strategies for Getting the Most Out of An Online Class.”

- Try brainstorming ways to find joy and “fun” again. This is useful both for you and your students. Try not to focus too much on “plans after the quarantine” because we really don’t know how long this will last, and we want to live in the present. Instead, you might think about reframing how we talk about celebration and joy-seeking. Perhaps it might be time for you and your students to enroll in Yale’s highly popular Happiness course, now available online and open to all. Find it here. (You might benefit from this course along with your students).

- If you know a student who will be missing their commencement ceremony, find a way to celebrate their accomplishment differently. Personally, we have always wanted to see a better way, one which doesn’t involve hours of pomp and circumstance for a single moment of celebration when your graduate’s name is called. This is an opportunity to make it personal and even more memorable. For some ideas and suggestions, click on the following: How to Plan a Personal Commencement Ceremony for Your Graduate.

- Help a student make important connections to professionals in the workforce who may be able to offer them an internship or job. Perhaps hold a special Zoom session to discuss professionalizing materials. Write letters of recommendation for students. If you have the means to do so, buy them a LinkedIn membership, their own URL and website, or membership to a professional organization of their choice.

- Help students navigate financial aid and scholarship applications. If you are in the incredibly privileged place to do so, help students with their college expenses and debt.

- Recognize that their professors with whom they may have had significant mentor relationships with are not able to meet with them in-person. Find ways to connect with students meaningfully despite this lack of in-person dynamic.

- Mentor your student. Teach them all you know. Perhaps most importantly, teach them through modeling how to be an empathetic, compassionate human in this time of uncertainty and anxiety.

One of our favorite metonyms for thinking about good teaching comes from a scene in the film Hook when a grown up Peter Pan, played by Robin Williams, returns to Neverland. Because he’s now grown, none of the “Lost Boys” believe that the grown up “Peter” is the same “Peter Pan” they once knew and loved. The Lost Boys must look past what they think they know about Peter to come to appreciate the reality, and more importantly, to connect with who Peter is now. Watch the short scene here.

Remembering what it’s like to “not know something,” is one of the best ways to think about how to be a good teacher, in part because it asks us to remember what it felt like to be a student, what it felt like to be in uncertain waters (we can relate to this presently, yes?). You have to perhaps look past what your initial perceptions are – of students and of this new teaching experience alike – to appreciate what’s underneath. When the Lost Boy from this scene of Hook places his hands on Peter’s face, it’s an act of great care and an act that shows a willingness to understand, to know. This Lost Boy makes the extra effort to look deeper when all the other Lost Boys were ready to dismiss Peter. With this extra effort, the Lost Boy helps Peter smile, physically lifting up the corners of his face to do so. It’s from this connection, this gesture of goodness, of willingness, of openness that Peter experiences the joy, and the Lost Boy says, “Oh there you are Peter.” … This is how we should care for our college students. Make the effort, no matter how difficult it may be, to connect with the soul of the person inside. Make our students feel seen. Make them smile.

It was easy for many people to criticize Mr. Sluder when he made his comments during his spring break in Florida. On March 22, 2020, he authored this post in Instagram:

I’ve done a lot of things in my life that I’m not proud of. I’ve failed, I’ve let down, and I’ve made plenty of mistakes. I can’t apologize enough to the people i’ve offended and the lives I’ve insulted. I’m not asking for your forgiveness, or pity. I want to use this as motivation to become a better person, a better son, a better friend, and a better citizen. Listen to your communities and do as health officials say. Life is precious. Don’t be arrogant and think you’re invincible like myself. I’ve learned from these trying times and I’ve felt the repercussions to the fullest. Unfortunately, simply apologizing doesn’t justify my behavior. I’m simply owning up to my mistakes and taking full responsibility for my actions. Thank you for your time, and stay safe everyone. ❤️

As of April 6, 2020, his words had 13.9k hearts, including ours. We need to have empathy for our students and ourselves. We need to acknowledge what an unprecedented moment we’re living through, and we need to have patience and understanding as we carefully navigate that landscape, sometimes missing the mark, but trying to make it right when we do.

Let’s try to help our college students be better people during this time. The best way to do that, perhaps, is to try to be better people ourselves.

Professor David C. Pecoraro, M.F.A. – Co-Founder, The Student Caring Project

Dr. Shannon Hervey, Ph.D. – Lecturer, Stanford University, Program in Writing and Rhetoric

0 Comments